Sunday, December 30, 2018

Tuesday, December 25, 2018

Saturday, December 22, 2018

2(h)Argyris Summary

Psychologist Chris Argyris and philosopher Donald Schön's intervention research focused on exploring the ways organisations can increase their capacity for double-loop learning. They argued that double-loop learning is necessary if organisations and its members are to manage problems effectively that originate in rapidly changing and uncertain contexts.

Argyris and Schön distinguished three levels of learning in organisations.

1. SINGLE-LOOP learning

"Adaptive learning" focuses on incremental change. This type of learning solves problems but ignores the question of why the problem arose in the first place.

2. DOUBLE-LOOP learning

Generative learning focuses on transformational change that changes the status quo. Double loop learning uses feedback from past actions to question assumptions underlying current views. When considering feedback, managers and professionals need to ask not only the reasons for their current actions, but what to do next and even more importantly, why alternative actions are not to be implemented.

3. DEUTERO-learning

Learning how to learn better by seeking to improve both single- and double-loop learning.

People's tacit mental maps provide guidance on acting in situations: planning, implementing and reviewing their actions. Learning is based on the detection and correction of errors given a current set of norms, the applied action strategy and the realised outcome.

Argyris and Schön regarded individuals as the key to organisational learning. People constructing and sharing mental maps make the development of organisational memory and learning possible.

The theory-in-action concept of the two researchers substantiated that a gap exists between what individuals say they want to do (espoused theory) and what they actually do (theory in use). People always behave consistently with their mental models (theory-in-use) even though they often do not act in accordance with what they say (espoused theory). This concept is useful in understanding organisational behaviour and change processes.

Top management issuing orders, memos and directives alone is insufficient to change employees' behaviour. Single-loop learning often leads to organisational malaise resulting in symptoms such as defensiveness, cynicism, hopelessness, evasion, distancing, blaming, and rivalry.

In order to effectively come to grips with new situations, the espoused theories need to be aligned with the theories in use. Double-loop learning techniques help the organisation members learn together and the organisation change.

pros:

The model helps conceptualise organisational learning by overcoming the taken-for-granted aspects of organisations and by detecting and solving structural problems.

Double loop learning emphasised that ideas, even from valued experts, should never be accepted at face value. Experience of employees within and specific to the organisation, creates real change.

cons:

Organisational change occurs when behavioural defences by individuals and groups are overcome and new interactions take place. This perspective overlooks the role systems and structures play in change processes.

2(h) Argyris Single and Double Loop Learning

These conceptual frameworks have implications for our learning processes. As mentioned previously, the consequences of an action may be intended or unintended. When the consequences of the strategy employed are as the person intends, then there is a match between intention and outcome. Therefore the theory-in-use is confirmed. However, the consequences may be unintended, and more particularly they may be counterproductive to satisfying their governing values. In this case there is a mismatch between intention and outcome. Argyris and Schon suggest that there are two possible responses to this mismatch, and these are represented in the concept of single and double-loop learning.

Single-loop and Double-loop learning

It is suggested (Argyris, Putnam & McLain Smith, 1985) that the first response to this mismatch between intention and outcome is to search for another strategy which will satisfy the governing variables.

For example a new strategy in order to suppress conflict might be to reprimand the other people involved for wasting time, and suggest they get on with the task at hand. This may suppress the conflict and allow feelings of competence as the fault has been laid at the feet of the other party for wasting time. In such a case the new action strategy is used in order to satisfy the existing governing variable. The change is in the action only, not in the governing variable itself. Such a process is called single-loop learning. See Figure 3.

Another possible response would be to examine and change the governing values themselves. For example, the person might choose to critically examine the governing value of suppressing conflict. This may lead to discarding this value and substituting a new value such as open inquiry. The associated action strategy might be to discuss the issue openly. Therefore in this case both the governing variable and the action strategy have changed. This would constitute double-loop learning. See Figure 3.

Figure 3. Single and double-loop learning

In this sense single and double-loop learning bear close resemblance to what Watzlawick, Weakland and Fisch (1974) call First and Second Order Change. First Order Change exists when the norms of the system remain the same and changes are made within the existing norms. Second Order Change describes a situation where the norms of the system themselves are challenged and changed.

Double-loop learning is seen as the more effective way of making informed decisions about the way we design and implement action (Argyris, 1974).

Consequently, Argyris and Schon's approach is to focus on double-loop learning. To this end, they developed a model that describes features of theories-in-use which either inhibit or enhance double-loop learning. Interestingly, Argyris suggests that there is a large variability in Espoused theories and Action strategies, but almost no variability in Theories-in-use. He suggests people may espouse a large number and variety of theories or values which they suggest guide their action. However Argyris believes that the theories which can be deduced from peoples' action (theories-in-use) seem to fall into two categories which he labels Model I and Model II.

The governing values associated with theories-in-use can be grouped into those which inhibit double-loop learning (Model I) and those which enhance it (Model II).

Models I and II

Model I is the group which has been identified as inhibiting double-loop learning. It has been described as being predominantly competitive and defensive (Dick & Dalmau, 1990). The defining characteristics of Model I are summarised in Table 1.

Argyris claimed that virtually all individuals in his studies operated from theories-in-use or values consistent with Model I (Argyris et al. 1985, p. 89). Argyris also suggests most of our social systems are Model I. This assumption implies predictions about the kinds of strategies people will employ, and about the resulting consequences. These predictions have been tested repeatedly by Argyris and not been disconfirmed (Argyris, 1982, Chap. 3), though I am unaware of studies by anyone other than Argyris which have tested these predictions.

The governing Values of Model I are:

Table 1. Model I theory-in-use characteristics

Primary Strategies are:

- Achieve the purpose as the actor defines it

- Win, do not lose

- Suppress negative feelings

- Emphasise rationality

Usually operationalised by:

- Control environment and task unilaterally

- Protect self and others unilaterally

Consequences include:

- Unillustrated attributions and evaluations eg. "You seem unmotivated"

- Advocating courses of action which discourage inquiry eg. "Lets not talk about the past, that's over."

- Treating ones' own views as obviously correct

- Making covert attributions and evaluations

- Face-saving moves such as leaving potentially embarrassing facts unstated

_____

- Defensive relationships

- Low freedom of choice

- Reduced production of valid information

- Little public testing of ideas

Taken from Argyris, Putnam & McLain Smith (1985, p. 89).

The Model I world view is a theory of single loop learning according to Argyris and Schon. Therefore Model I has the effect of restricting a person to single-loop learning. Being unaware of what is driving one's behaviour may seriously inhibit the likelihood of increased effectiveness in the long-term.

Argyris (1980) suggests that (as mentioned previously) the primary action strategy of Model I is: unilateral control of the environment and task, and unilateral protection of self and others. The underlying strategy is control over others. Such control inhibits communication and can produce defensiveness. Defensiveness is a mechanism used in order to protect the individual. Model I theory-in-use informs individuals how to design and use defences unilaterally, whether to protect themselves or others, eg. "I couldn't tell him the truth, it would hurt him too much".

In order to protect themselves individuals must distort reality. Such distortion is usually coupled with defences which are designed to keep themselves and others unaware of their defensive reaction (Argyris, 1980). The more people expose their thoughts and feelings the more vulnerable they become to the reactions of others. This is particularly true if these others are programmed with Model I theory-in-use and are seeking to maximise winning.

The assertion that Model I is predominantly defensive has another ramification. Acting defensively can be viewed as moving away from something, usually some truth about ourselves. If our actions are driven by moving away from something then our actions are controlled and defined by whatever it is we are moving away from, not by us and what we would like to be moving towards. Therefore our potential for growth and learning is seriously impaired. If my behaviour is driven by my not wanting to be seen as incompetent, this may lead me to hide things from myself and others, in order to avoid feelings of incompetence. For example, if my behaviour is driven by wanting to be competent, honest evaluation of my behaviour by myself and others would be welcome and useful.

In summary, Model I has been identified as a grouping of characteristics which inhibit double-loop learning. Model I is seen as being predominantly defensive and competitive, and therefore unlikely to allow an honest evaluation of the actor's motives and strategies, and less likely to lead to growth. Defensiveness protects individuals from discovering embarrassing truths about their incongruent or less-than-perfect behaviour and intentions. The actor further protects herself by reinforcing conditions such as ambiguity and inconsistency which help to further mask their incongruence from themselves and others. Becoming aware of this incongruence is difficult, as is doing something about it. According to Argyris and Schon (1974) this is due to the strength of the socialisation to Model I, and the fact that the prevailing culture in most systems is Model I. An added complication is that anyone trying to inform them of the incongruence is likely to use Model I behaviour to do so, and therefore trigger a defensive reaction (Dick and Dalmau, 1990).

Therefore, Model I theories-in-use are likely to inhibit double-loop learning for the following reasons. Model I is characterised by unilateral control and protection, and maximising winning. In order to maintain these, the actor is often involved in distortion of the facts, attributions and evaluations, and face-saving. Doing such things is not something we would readily admit we involve ourselves in. Therefore, in order to live with ourselves we put in place defences which hamper our discovery of the truth about ourselves. If we are unwilling to admit to our motives and intentions we are hardly in a position to evaluate them. As evaluating our governing values (which may be equated with intentions) is what characterises double-loop learning, Model I theories-in-use may be seen as inhibiting this process.

Despite all the evidence which suggests that peoples' theory-in-use is consistent with Model I, Argyris has found that most people hold espoused theories which are inconsistent with Model I. Most people in fact, espouse Model II, according to Argyris. The defining characteristics of Model II are summarised in Table 2.

The governing values of Model II include:

Table 2. Model II

Strategies include:

- "Valid information

- Free and informed choice

- Internal commitment

Operationalised by:

- Sharing control

- Participation in design and implementation of action

Consequences should include:

- Attribution and evaluation illustrated with relatively directly observable data

- Surfacing conflicting views

- encouraging public testing of evaluations

- Minimally defensive relationships

- high freedom of choice

- increased likelihood of double-loop learning"

No reason is offered for why most people espouse Model II, however it seems reasonable to assume that this is because Model II values are the more palatable in terms of the way we like to see our (Western) society. Freedom of Information Acts, the Constitution, America's bill of Rights, all seem to be drawing heavily from Model II values. Dick and Dalmau (1990) suggest that people often show a mix of Model I and Model II espoused theories. This seems probable, as most people will readily admit to being driven to win at least in some situations. Some professions in fact, are based almost entirely around the concept of winning and not losing, such as Law, sport and sales.

The behaviour required to satisfy the governing values of Model II though, are not opposite to that of Model I. For instance, the opposite of being highly controlling would be to relinquish control altogether. This is not Model II behaviour because Model II suggest bilateral control. Relinquishing control is still unilateral, but in the other direction. Model II combines articulateness about one's goals and advocacy of one's own position, with an invitation to others to confront one's views. It therefore produces an outcome which is based on the most complete and valid information possible. Therefore,

"Every significant Model II action is evaluated in terms of the degree to which it helps the individuals involved generate valid and useful information (including relevant feelings), solve the problem in a way that it remains solved, and do so without reducing the present level of problem solving effectiveness." (Argyris, 1976, p21-22)

If we go back to the information chain model put forward by Dick and Dalmau (Figure 2), valid information has to do with expressing our beliefs, feelings, and intentions (the highlighted area in Figure 2).

Given the above considerations, the consequences for learning should be an emphasis on double-loop learning, in which the basic assumptions behind views are confronted, hypotheses are tested publicly, and processes are disconfirmable, not self-sealing. The end result should be increased effectiveness.

Important Links

http://www.westbrookstevens.com/Researchers.htm

https://www.provenmodels.com/41/technology-typology/charles-b.-perrow

http://www.aral.com.au/resources/argyris.html

https://www.provenmodels.com/41/technology-typology/charles-b.-perrow

http://www.aral.com.au/resources/argyris.html

Friday, December 21, 2018

Thursday, December 20, 2018

2(h)-Models of Organisational Influence

- This is the third in a series of posts adapted from Scott Keller & Colin Price's new book,Beyond Performance: How Great Organizations Build Ultimate Competitive Advantage. The first post described two counter-intuitive insights about creating lasting change in organizations -- that common sense can sometimes lead you astray, and that the "soft" stuff can be managed as rigorously as the "hard" stuff in organizations.

- The second post discussed ways to use social media and viral marketing within organizations to sustain change programs.

- You know your organization needs to change. You've developed a strategic view about where you need to go and you've matched that up with an understanding of the changes that will require in your culture.

- You've thought very hard about organizational mindsets and personal behaviors that will need to shift to get there. Now, you actually have to do something to shift them.

- Getting anyone to change is hard. Getting a whole organization to change can seem nearly impossible.

- Yet that's exactly what most organizations need to do to continue to thrive.

- Over a few decades of working with all kinds of organizations--businesses, government agencies, NGOs--we've developed a process to encourage people to change that works. Not all the time, but far more often than not.

- In more than a decade of research and far more client work, what we've seen is that the starkest differentiation between organizations that can change successfully (and sustain higher performance over time) and all the others isn't in what they say, it's in what they do--how they actually implement change.

- You can't just have a workshop and put up a few posters, you have to intervene in the system.

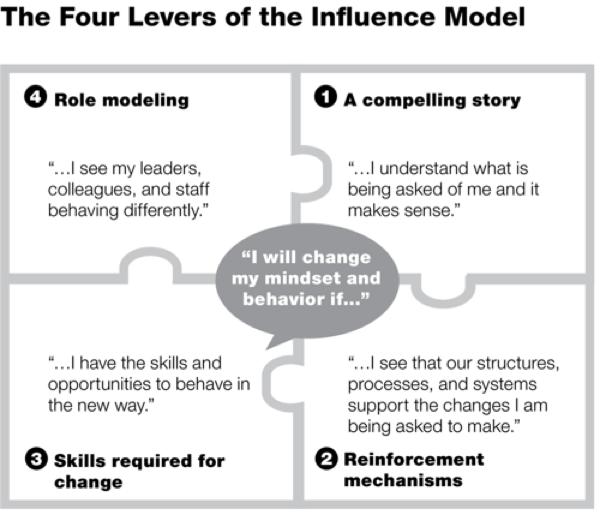

We think about it this way: if you want to change someone's behavior just imagine you're in the middle of this square. There are four things that need to happen, and they need to happen in relative symmetry.

Most people have been behaving however they behave for a long time.

At work, very often those ingrained behaviors are reinforced by the organization's culture and by how its leaders behave.

1.What is asked from Employees-

So, the first step, top right hand side, people need to understand what you want them to do differently. And they need to get that at least enough to be willing to experiment. That can take anywhere between two days and a year. It's not just sending out a memo and assuming it's done. It's a process of deeply engaging with people, talking with them, listening to them, framing the changes in a context that's meaningful to them

2.Reinforcement Mechanisms

Next, bottom right, if people understand the strategy and understand the desired culture, but look around and see the systems and processes of the organization reinforcing yesterday rather than tomorrow, they think all that dialog isn't serious. If we're supposed to act with speed and urgency but the budget process takes three months, people will think, "Oh well, why bother? It's just not real." Now, there are thousands of processes in any large organization, so you can't change them all. But you can choose the five or ten that will have most leverage on the outcome and change those very early on.

3.Skills Required for Change

Bottom left is about capabilities. People may want to change, and see processes changing around them, but they personally also have to have the skills to behave differently. Maybe that's different technical skills, maybe it's different leadership skills. For the organization, that gets you into placement, replacement, and development. Placement is moving people around, replacement is moving people out in the appropriate way, and development is helping people in place gain new skills.

4.Role Modelling-

And then top left. Psychologists would tell us that this is as important as the other three added together, and it's that people need to see significant others, usually the senior people, role modeling new behaviors, following new processes, building new capabilities. If we're supposed to be more open to the external world, for example, is the CEO out there visiting customers?

***************************************************************************

***************************************************************************

Each of the four levers in our influence model affects mindsets in a particular way. An individual transformation program may rely on some levers more than others, but using all four together sets in motion a powerful system that maximizes a company's chances of getting new patterns of thought and behavior to stick.

To illustrate how the levers work together, imagine that you go to the opera on Saturday and a football game on Sunday. At the climax of the opera, you sit silent and rapt in concentration. At the climax of the football game, you leap to your feet, yelling and waving and jumping up and down. You haven't changed, but your context has (the influence model that surrounds you)--and so has your mindset about the behavior that's appropriate for expressing your appreciation and enjoyment.

To continue with the analogy, organizations that are unhealthy are often caught between an opera house and a football stadium--not a comfortable place to be. Asking employees for a football-stadium mindset is no use if your evaluation systems and leadership actions communicate that your organization is still an opera house. If you want your people to think like football fans, you need to provide plenty of cues to remind them they are in a stadium.

To illustrate how the levers work together, imagine that you go to the opera on Saturday and a football game on Sunday. At the climax of the opera, you sit silent and rapt in concentration. At the climax of the football game, you leap to your feet, yelling and waving and jumping up and down. You haven't changed, but your context has (the influence model that surrounds you)--and so has your mindset about the behavior that's appropriate for expressing your appreciation and enjoyment.

To continue with the analogy, organizations that are unhealthy are often caught between an opera house and a football stadium--not a comfortable place to be. Asking employees for a football-stadium mindset is no use if your evaluation systems and leadership actions communicate that your organization is still an opera house. If you want your people to think like football fans, you need to provide plenty of cues to remind them they are in a stadium.

Tuesday, December 18, 2018

Monday, December 17, 2018

Saturday, December 15, 2018

3(d)Douglas Macgregor

Organizational Behaviour in the context of people management consists of several theories in which Theory X, Theory Y, Theory Z are the newly introduced. Theory X and Y were created and developed by Douglas McGregor in the 1960s. Theory X says that the average human being is lazy and self-centred, lacks ambition, dislikes change, and longs to be told what to do. Theory Y maintains that human beings are active rather than passive shapers of themselves and of their environment. They long to grow and assume responsibility. The best way to manage them, is to manage as little as possible. Theory Z of William Ouchi focused on increasing employee loyalty to the company by providing a job for life with a strong focus on the wellbeing of the employee, both on and off the job. The above three theories were developed based on research conducted in various production related organizations in 20th century. In 21st century, due to changes in business models, automation of production process, changes in technology & business environment, and changes in people perception, organizations are transforming into global entities - a new theory in organizational behaviour called Theory A (Theory of Accountability) has been developed.

Ouchi’s Theory Z

During the 1980s, American business and industry experienced a tsunami of demand for Japanese products and imports, particularly in the automotive industry. Why were U.S. consumers clambering for cars, televisions, stereos, and electronics from Japan? Two reasons: (1) high-quality products and (2) low prices. The Japanese had discovered something that was giving them the competitive edge. The secret to their success was not what they were producing but how they were managing their people—Japanese employees were engaged, empowered, and highly productive.

Management professor William Ouchi argued that Western organizations could learn from their Japanese counterparts. Although born and educated in America, Ouchi was of Japanese descent and spent a lot of time in Japan studying the country’s approach to workplace teamwork and participative management. The result was Theory Z—a development beyond Theory X and Theory Y that blended the best of Eastern and Western management practices. Ouchi’s theory first appeared in his 1981 book, Theory Z: How American Management Can Meet the Japanese Challenge. The benefits of Theory Z, Ouchi claimed, would be reduced employee turnover, increased commitment, improved morale and job satisfaction, and drastic increases in productivity.

Theory Z stresses the need to help workers become generalists, rather than specialists. It views job rotations and continual training as a means of increasing employees’ knowledge of the company and its processes while building a variety of skills and abilities. Since workers are given much more time to receive training, rotate through jobs, and master the intricacies of the company’s operations, promotions tend to be slower. The rationale for the drawn-out time frame is that it helps develop a more dedicated, loyal, and permanent workforce, which benefits the company; the employees, meanwhile, have the opportunity to fully develop their careers at one company. When employees rise to a higher level of management, it is expected that they will use Theory Z to “bring up,” train, and develop other employees in a similar fashion.

Ouchi’s Theory Z makes certain assumptions about workers. One assumption is that they seek to build cooperative and intimate working relationships with their coworkers. In other words, employees have a strong desire for affiliation. Another assumption is that workers expect reciprocity and support from the company. According to Theory Z, people want to maintain a work-life balance, and they value a working environment in which things like family, culture, and traditions are considered to be just as important as the work itself. Under Theory Z management, not only do workers have a sense of cohesion with their fellow workers, they also develop a sense of order, discipline, and a moral obligation to work hard. Finally, Theory Z assumes that given the right management support, workers can be trusted to do their jobs to their utmost ability and look after for their own and others’ well-being.

Theory Z also makes assumptions about company culture. If a company wants to realize the benefits described above, it need to have the following:

A strong company philosophy and culture: The company philosophy and culture need to be understood and embodied by all employees, and employees need to believe in the work they’re doing.

- Long-term staff development and employment: The organization and management team need to have measures and programs in place to develop employees. Employment is usually long-term, and promotion is steady and measured. This leads to loyalty from team members.

- Consensus in decisions: Employees are encouraged and expected to take part in organizational decisions.

- Generalist employees: Because employees have a greater responsibility in making decisions and understand all aspects of the organization, they ought to be generalists. However, employees are still expected to have specialized career responsibilities.

- Concern for the happiness and well-being of workers: The organization shows sincere concern for the health and happiness of its employees and their families. It takes measures and creates programs to help foster this happiness and well-being.

- Informal control with formalized measures: Employees are empowered to perform tasks the way they see fit, and management is quite hands-off. However, there should be formalized measures in place to assess work quality and performance.

- Individual responsibility: The organization recognizes the individual contributions but always within the context of the team as a whole.

Theory Z is not the last word on management, however, as it does have its limitations. It can be difficult for organizations and employees to make life-time employment commitments. Also, participative decision-making may not always be feasible or successful due to the nature of the work or the willingness of the workers. Slow promotions, group decision-making, and life-time employment may not be a good fit with companies operating in cultural, social, and economic environments where those work practices are not the norm.

Maslow Theory Z

Theory W

- A software project management theory is presented called Theory W: make everyone a winner.

- The authors explain the key steps and guidelines underlying the Theory W statement and its two subsidiary principles: plan the flight and fly the plan;

- and, identify and manage your risks.

- Theory W's fundamental principle holds that software project managers will be fully successful if and only if they make winners of all the other participants in the software process: superiors, subordinates, customers, users, maintainers, etc.

- Theory W characterizes a manager's primary role as a negotiator between his various constituencies, and a packager of project solutions with win conditions for all parties.

- Beyond this, the manager is also a goal-setter, a monitor of progress towards goals, and an activist in seeking out day-to-day win-lose or lose-lose project conflicts confronting them, and changing them into win-win situations.

- Several examples illustrate the application of Theory W.

- An extensive case study is presented and analyzed: the attempt to introduce new information systems to a large industrial corporation in an emerging nation.

- The analysis shows that Theory W and its subsidiary principles do an effective job both in explaining why the project encountered problems, and in prescribing ways in which the problems could have been avoided.

2(C) Karl Marx And Bureaucracy

The Rheinische Zeitung ("Rhenish Newspaper") was a 19th-century Germannewspaper, edited most famously by Karl Marx. The paper was launched in January 1842 and terminated by Prussian state censorship in March 1843

Saturday, December 8, 2018

Friday, December 7, 2018

3(d) David McClelland Needs Theory

In the early 1940s, Abraham Maslow created his theory of needs. This identified the basic needs that human beings have, in order of their importance: physiological needs, safety needs, and the needs for belonging, self-esteem and "self-actualization".

Later, David McClelland built on this work in his 1961 book, "The Achieving Society." He identified three motivators that he believed we all have: a need for achievement, a need for affiliation, and a need for power. People will have different characteristics depending on their dominant motivator.

According to McClelland, these motivators are learned (which is why this theory is sometimes called the Learned Needs Theory).

McClelland says that, regardless of our gender, culture, or age, we all have three motivating drivers, and one of these will be our dominant motivating driver. This dominant motivator is largely dependent on our culture and life experiences.

These characteristics are as follows:

| Dominant Motivator | Characteristics of This Person |

|---|---|

| Achievement |

|

| Affiliation |

|

| Power |

|

Note:

Those with a strong power motivator are often divided into two groups: personal and institutional. People with a personal power drive want to control others, while people with an institutional power drive like to organize the efforts of a team to further the company's goals. As you can probably imagine, those with an institutional power need are usually more desirable as team members!

Using the Theory

McClelland's theory can help you to identify the dominant motivators of people on your team. You can then use this information to influence how you set goals and provide feedback, and how you motivate and reward team members.

You can also use these motivators to craft, or design, the job around your team members, ensuring a better fit.

Let's look at the steps for using McClelland's theory:

Step 1: Identify Drivers

Examine your team to determine which of the three motivators is dominant for each person. You can probably identify drivers based on personality and past actions.

For instance, perhaps one of your team members always takes charge of the group when you assign a project. He speaks up in meetings to persuade people, and he delegates responsibilities to others to meet the goals of the group. He likes to be in control of the final deliverables. This team member is likely primarily driven by the power.

You might have another team member who never speaks during meetings. She always agrees with the group, works hard to manage conflict when it occurs, and visibly becomes uncomfortable when you talk about doing high-risk, high-reward projects. This person is likely to have a strong need for affiliation.

Step 2: Structure Your Approach

Based on the driving motivators of your workers, structure your leadership style and project assignments around each individual team member. This will help ensure that they all stay engaged, motivated, and happy with the work they're doing.

Examples of Using the Theory

Let's take a closer look at how to manage team members who are driven by each of McClelland's three motivators:

Achievement

People motivated by achievement need challenging, but not impossible, projects. They thrive on overcoming difficult problems or situations, so make sure you keep them engaged this way. People motivated by achievement work very effectively either alone or with other high achievers.

When providing feedback, give achievers a fair and balanced appraisal. They want to know what they're doing right – and wrong – so that they can improve.

Affiliation

People motivated by affiliation work best in a group environment, so try to integrate them with a team (versus working alone) whenever possible. They also don't like uncertainty and risk. Therefore, when assigning projects or tasks, save the risky ones for other people.

When providing feedback to these people, be personal. It's still important to give balanced feedback, but if you start your appraisal by emphasizing their good working relationship and your trust in them, they'll likely be more open to what you say. Remember that these people often don't want to stand out, so it might be best to praise them in private rather than in front of others.

Power

Those with a high need for power work best when they're in charge. Because they enjoy competition, they do well with goal-oriented projects or tasks. They may also be very effective in negotiations or in situations in which another party must be convinced of an idea or goal.

When providing feedback, be direct with these team members. And keep them motivated by helping them further their career goals.

Comparative Theories

McClelland's theory of needs is not the only theory about worker motivation. Sirota's Three-Factor Theory also presents three motivating factors that workers need to stay motivated and excited about what they're doing: equity/fairness, achievement, and camaraderie.

Sirota's theory states that we all start a new job with lots of enthusiasm and motivation to do well. But over time, due to bad company policies and poor work conditions, many of us lose our motivation and excitement.

This is different from McClelland's theory, which states that we all have one dominant motivator that moves us forward, and this motivator is based on our culture and life experiences.

Use your best judgment when motivating and engaging your team. Understanding a variety of motivational theorieswill help you decide which approach is best in any given situation.

Note:

You may also see these abbreviations for McClelland's three motivators: Achievement (nAch), Affiliation (nAff), and Power (nPow).

Key Points

McClelland's Human Motivation Theory states that every person has one of three main driving motivators: the needs for achievement, affiliation, or power. These motivators are not inherent; we develop them through our culture and life experiences.

Achievers like to solve problems and achieve goals. Those with a strong need for affiliation don't like to stand out or take risk, and they value relationships above anything else. Those with a strong power motivator like to control others and be in charge.

You can use this information to lead, praise, and motivate your team more effectively, and to better structure your team's roles.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

-

The American sociologist, Charles Perrow, developed a classification scheme based on the knowledge required to operate technology. Technol...

-

Models of Organisation: Closed and Open Models Read this article to learn about the closed and open models of an organiz...

-

The Rheinische Zeitung ("Rhenish Newspaper ") was a 19th-century German newspaper , edited most famously by Karl Marx . The ...